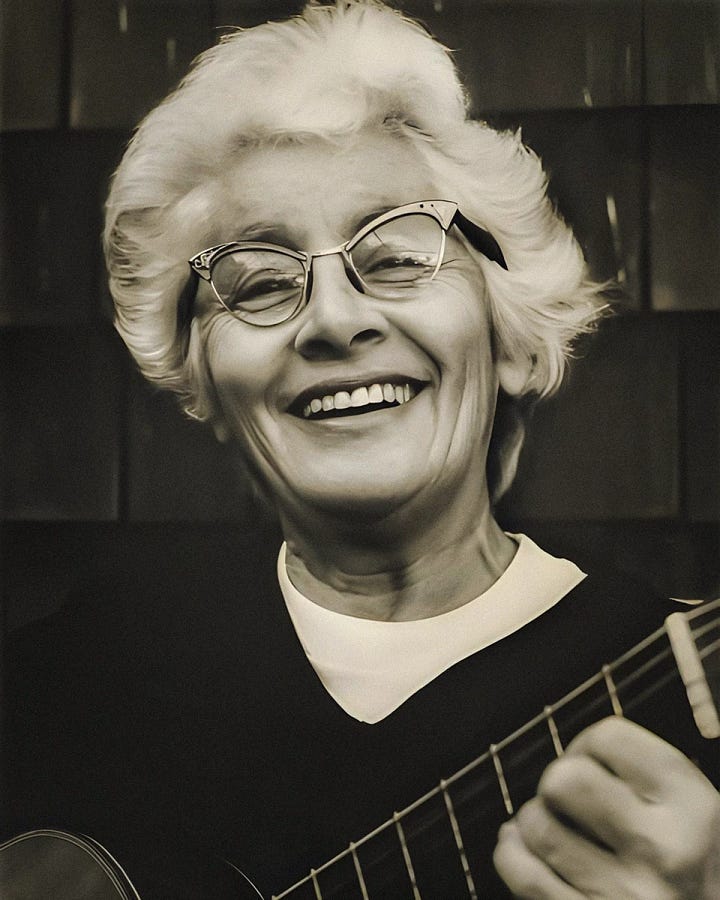

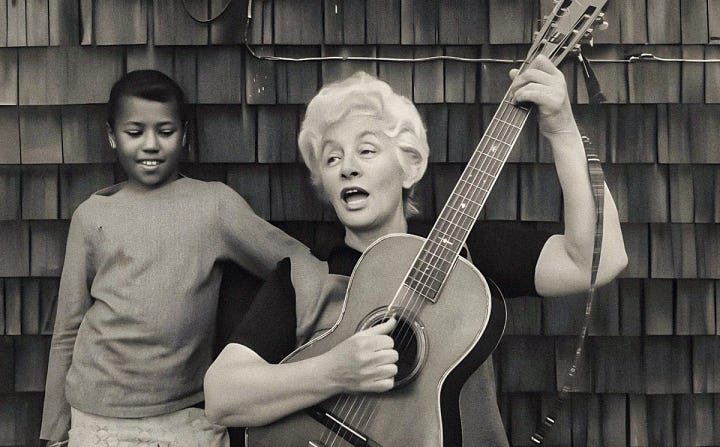

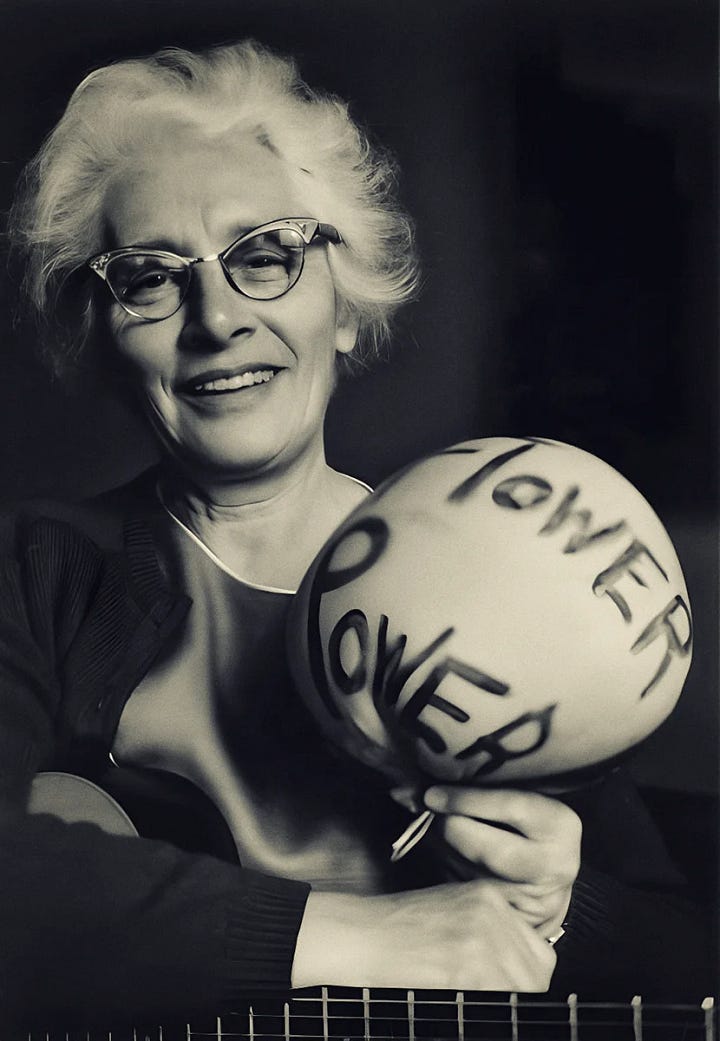

Malvina Reynolds was a folk singer-songwriter who came to prominence through San Francisco's burgeoning counterculture scene of the late 1950s. She was known for her sharp social critiques and incisive wit, though, is perhaps best-remembered today for her song "Little Boxes" being used in the opening for the 2005 show, Weeds. Reynolds had already established herself as a notable voice in folk and activist circles by the late 1950s, but it was Pete Seeger's 1963 cover of the song that gave her the widest exposure to mainstream audiences for the decades until its association with Weeds, which then lead to its appearance in several other shows as well.

The New Restaurant

Malvina was never one to shy away from the uncomfortable truths of her time, and her gift for biting, evergreen commentary continues to be evident, particularly in one of her less popular tracks, "The New Restaurant". Written in the early-mid 1960s1, the song offers a pointed critique of consumerism and the constant craving for novelty, while effortlessly dissecting society's obsession with what’s trendy — at the expense of what’s genuine — in a way that’s proven itself depressingly accurate.

Below is a clip from episode 6 of Pete Seeger's TV show "Rainbow Quest"2 of Melvina singing "The New Restaurant", and a couple links to the album recording as well.

At its heart, "The New Restaurant" critiques the fetishization of the new and shiny, a phenomenon that has only grown more pronounced in the years since — in a world where products and ideas are marketed not for their substance but for their novelty, Reynolds’ observations feel prophetic. The obsession with being on the cutting edge — with having the latest products, following the newest diet, or… dining at the trendiest spot — has left us detached from authenticity, despite being the foundation of the marketing of each these things. What we consume, whether it be food or ideas, is increasingly artificial, carefully engineered to simulate satisfaction without ever truly delivering it. This is the backdrop against which the song’s final verse delivers its most biting critique. In just 4 lines, Reynolds encapsulates an entire critique of corporatism, ultra-processed food, and societal disconnection — themes that resonate even more deeply today than when the song was written.

Another generation will forget the taste of meat

These words, simple as they are, reflect a reality that grows more tangible every day. In the years since Reynolds penned them, vegetarianism and veganism have moved from fringe movements to mainstream markers of ethical, and whether anyone wants to admit it or not, cultural superiority. While there can be merit to reducing meat consumption for health or environmental reasons, the marketing surrounding plant-based diets often plays into the same cycle Reynolds critiques: the pursuit of a trend for the sake of signaling one’s virtues without getting any real value from whatever it is they’ve been convinced to partake. The rise of fake meat products, while innovative, mirrors this dynamic. Designed to mimic something real while promoting themselves as morally superior to it, while in some ways this is arguably true, these products almost seem to cater more to the performative aspects of ethical consumption than to the authentic pursuit of health or sustainability: the most popular faux-meats are, in several ways, actually worse for you than the real thing, and are 100% reliant on the grid for their production. Reynolds’ line captures the tension between embracing novelty and losing touch with something primal and real — the unmediated experience of food as it is and always has been, not as it’s engineered and marketed.

Of tomatoes from the garden and of bread that’s made of wheat

Continuing the theme of detachment, she reflects on the loss of connection to garden-grown produce and simple, whole foods. Food today, even when marketed as healthy or natural, is often far removed from its original form. Many who pride themselves on consuming organic or “clean” foods are still relying on products that are, in essence, ultra-processed. Vegan diets, for instance, are often built around foods that are as industrially engineered as the animal products they aim to replace.

In the second half of the line there’s the almost prescient mention of “bread that’s made from wheat”, which seems to anticipate the gluten-free craze of today. While some can genuinely benefit from avoiding gluten, much of the movement serves as a case study in following trends without critical thought. This, in turn, has created a paradox: the pursuit of health, in its modern form, often leads to diets that are just as industrially processed — and sometimes just as harmful — as the unhealthy diets they aim to replace.

And they’ll never even notice, when it’s plastic that they eat

During its time, this line was merely a metaphor for the artificiality of processed food. But looking through a modern lens, it describes a chilling reality of our current world. Today, the plastic we consume is not just metaphorical; it is literal, micro-plastics have infiltrated our food chain and bodies — and we still don't understand the long-term effects it will have on our health or environment… not that our food is exactly making us healthy in the first place. The allure of convenience has come at a steep price, and, as Reynolds predicted, many remain blissfully unaware that the food… is terrible.

Life is Like The Jungle

This detachment from what’s real ties directly into broader themes of corporatism and exploitation. In some ways, our modern food system parallels the horrors described in Upton Sinclair’s 1904 novel, The Jungle. In Sinclair’s time, the dangers of the food industry were immediate and obvious: tainted meat, inhumane working conditions, and unsanitary factories. These issues sparked public outrage because they were visible and undeniable — and most importantly: made the product more difficult to sell. Today, the dangers are more subtle but no less insidious, and interestingly enough, are still rooted in moving product more than having any real concern for the consumer.

Instead of rotten meat, we face foods so processed that their health risks emerge only after years of consumption, and very likely, over-consumption (which is a bit of a misnomer, as for many products, “over-consumption” is exactly the type of consumption they were designed to induce). Instead of dangerous working conditions, we have supply chains that exploit labor far from the public eye. And all of this is carefully concealed behind the veneer of health and innovation, perpetuated by marketing designed to make us feel good about our choices, even when it’s those very choices that are making us sick.

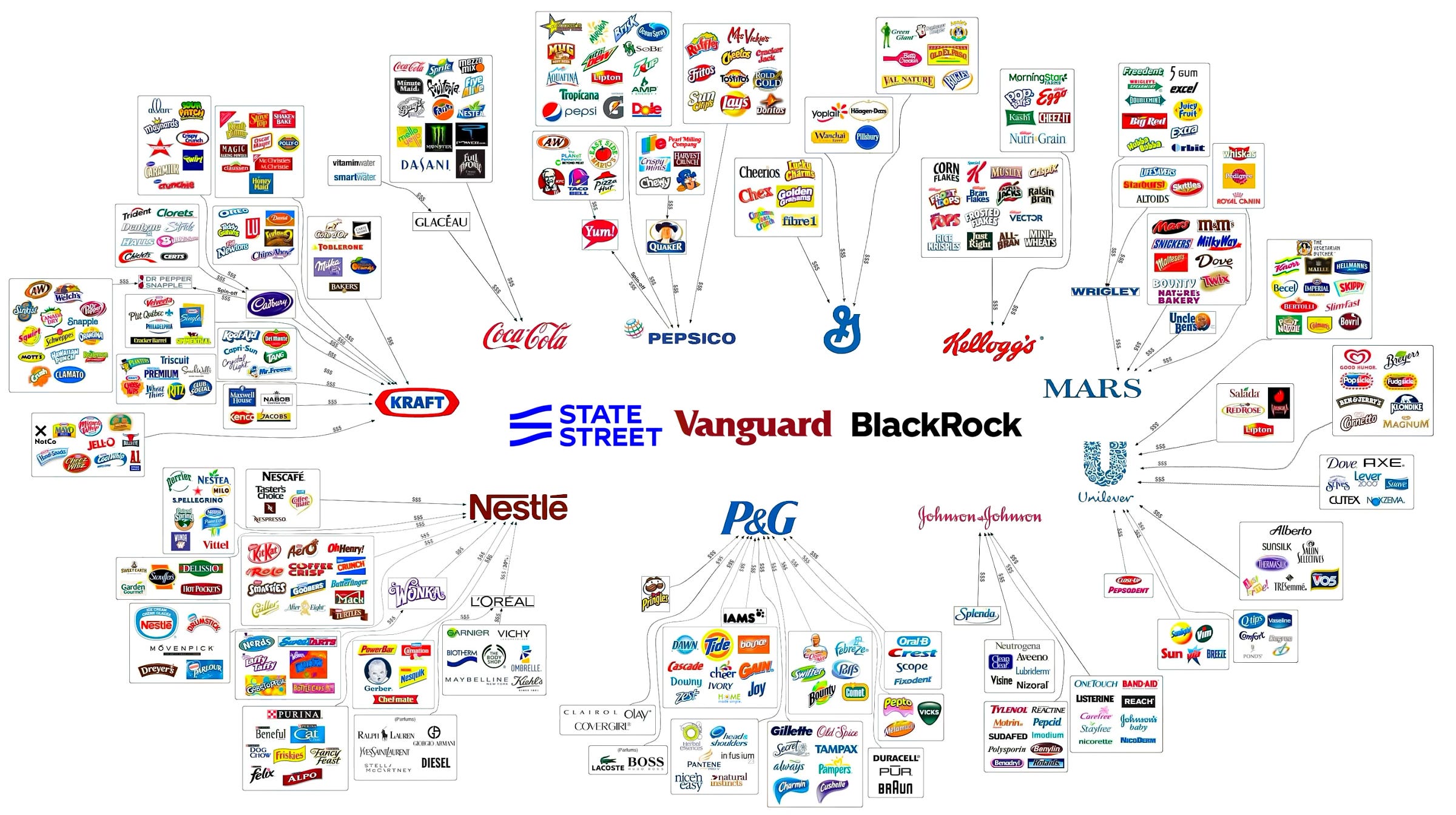

I Love Elvis / I Hate Elvis

What makes today’s situation even more dire is the corporate machinery that sustains it. Much like the famed Elvis promoter who sold both I love Elvis and I hate Elvis buttons, the very companies that profit from selling ultra-processed food are often the same ones that profit from the industries addressing the health crises these foods create. Pharmaceutical companies developing treatments for diabetes or heart disease are often owned by the same conglomerates that dominate the food industry. Even efforts to “eat healthier” are frequently funneled back into the same corporate coffers, as the biggest food companies own many of the brands marketed as natural or organic.

Of the top 10 U.S. pharmaceutical companies, at least six have significant institutional ownership by State Street, Vanguard, and BlackRock — who are also the top 3 stakeholders of each of the “Big 10” producers of consumer staples. Excluding accidental injuries and medical malpractice3 fighting for 3rd place, 8 of the remaining top 10 causes of death have links to ultra-processed foods produced by those companies. To put this into a little perspective, homicide would fall somewhere around 17th or 18th place.

It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that State Street, Vanguard, and BlackRock also control significant shares of each of the top 10 media companies in the U.S. —and just to go another level deeper: both Vanguard and BlackRock hold shares in State Street, and Vanguard and State Street hold shares in BlackRock (because of Vanguard's structure, it doesn't have external shareholders like BlackRock and State Street).

Society has been placed on a treadmill, dependent on industrialized convenience for sustenance while looking to the same institutions for help when the sustenance it offers inevitably makes us sick. The normalization of drugs like Ozempic4 is just the latest chapter in this story, a reflection of how this deeply-embedded cycle of dependency has become not only normalized, but glorified.

Malvina Reynolds saw through these dynamics long before they reached their current extremes. In just four lines, the final verse of "The New Restaurant" offers a critique that spans decades and continues to unfold today. It should be taken as a warning, not just about food, but about the systems that shape our lives, and about the need to resist the allure of what’s easy, trendy, or convenient.

IFRQ-FM

All tracks from every INFREQUENCY-FM playlist in one, long playlist. Just hit random & enjoy over 100 years of mostly lesser-known and obscure tracks from every decade from the 1910s to the 2020s!

while performed by several others for years after it was written, including Pete Seeger, it wasn’t until the 1967 album “Malvina Reynolds... Sings The Truth" that she released a recorded version of her own

filmed/aired sometime around mid 1965, couldn't find an exact date

which technically isn’t included in these lists for some reason, but in terms of numbers they are both fighting for 3rd place: UI for 2022 was 227,039 vs an estimate of 250,000 annually for MM

made by Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk with institutional support from…BlackRock & State Street

Excellent...thanks...except that meat is sooo good for us and we shouldn't be reducing it nor does it have the environmental impact you've been led to believe...after all Malvina spoke and sang about...you fell into the same trap.

I want to say thanks a lot and thanks a lot. Sarcastically because I just spent almost an hour watching Pete seeger Rambling Jack Elliot and Malvina Reynolds which was both great and bad rabbit hole internet!!!

But I love Malvina Reynolds and Freight Train has always spoke to me "please don't tell them which Train I'm on so they won't know where I've gone..."

I don't remember this one but I imagine covering it ....changing the line to "should" forget the taste of meat. Agree with you on most meat substitutes except things like homemade walnut burgers walnuts rolled oak eggs sage fine chopped fried in olive oil and tofu and tempeh which are high protein meat substitutes but long time not even thought about AS meat substitutes but just as nutritious food....

Anyway it was fun to see Malvina Reynolds.....thats at least the 2nd cheerful thing I've found today spending all day either "working hard" or "wasting time online" depending on how you see it. I'm telling me this is work since I'm practically a shut in with no other job now.

But the other parts of me think I'm wasting time jointing the Luddites Online" group!

American Dissident Artist Mr Dodo B Bird.

Dodobbird.pixels.com